“He was—and remains—a soloist in front of an orchestra, a player with the responsibility to interpret and add lustre to great works with variations of infinite subtlety and grace.”1

-James Hamilton

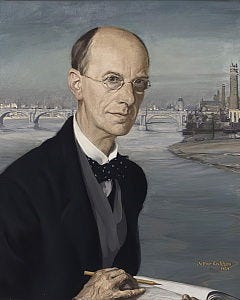

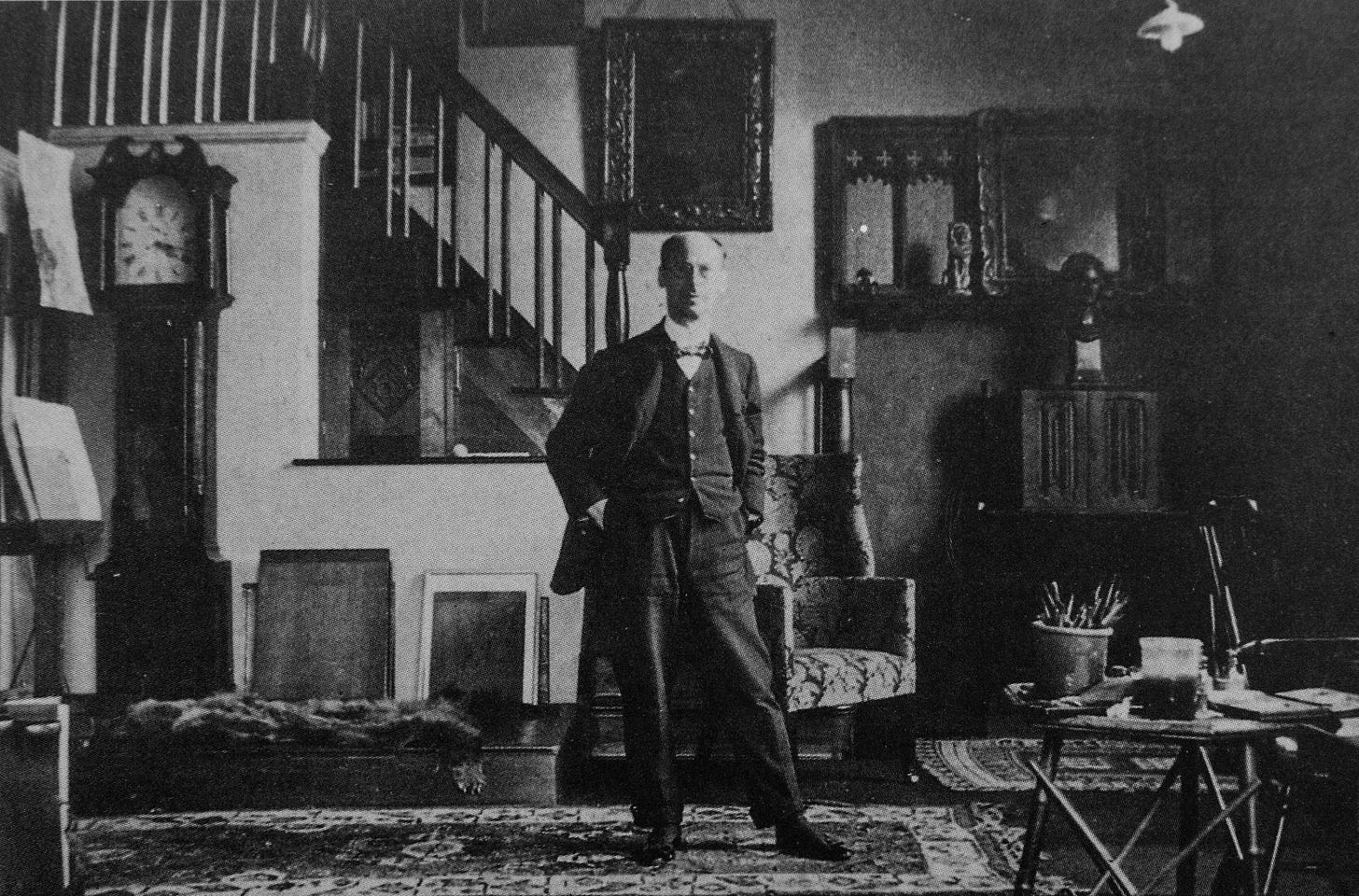

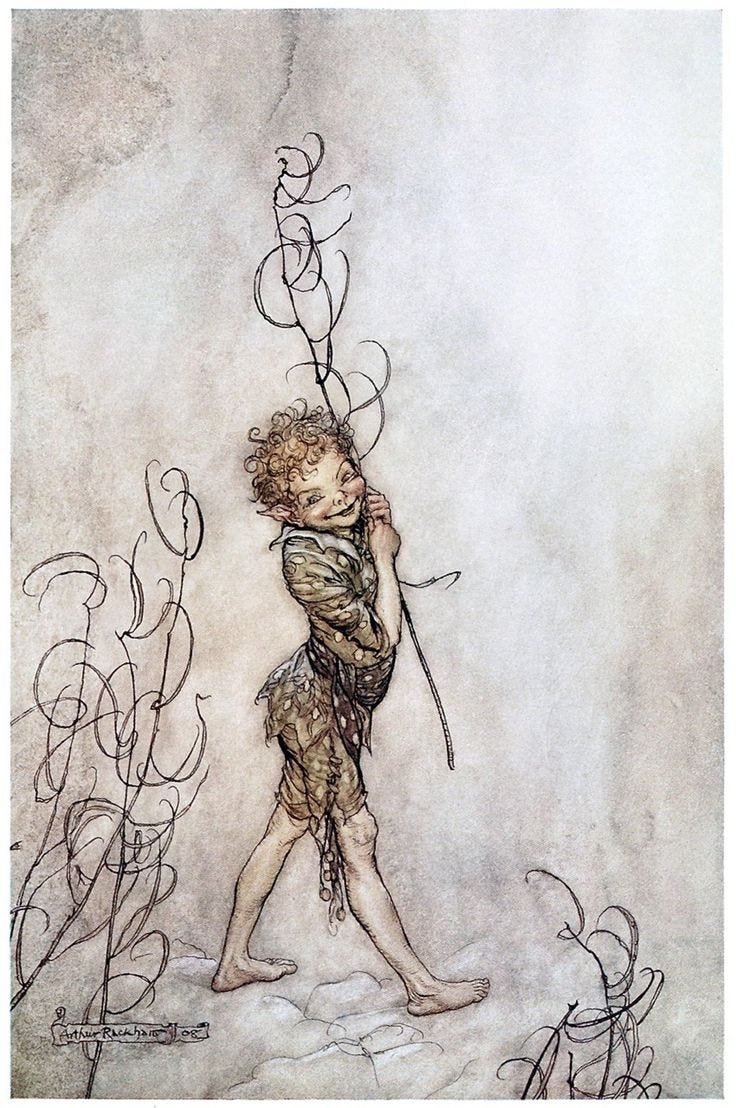

You may not know the name Arthur Rackham, but you have almost certainly seen—and loved—his artwork. One of the greatest illustrators of the modern world, Rackham illustrated many books, from Mother Goose to John Milton’s Comus, with great diversity in his subject matter. He has been fittingly called “The Goblin Master” and the “Court Painter to King Oberon & Queen Titiana.”2

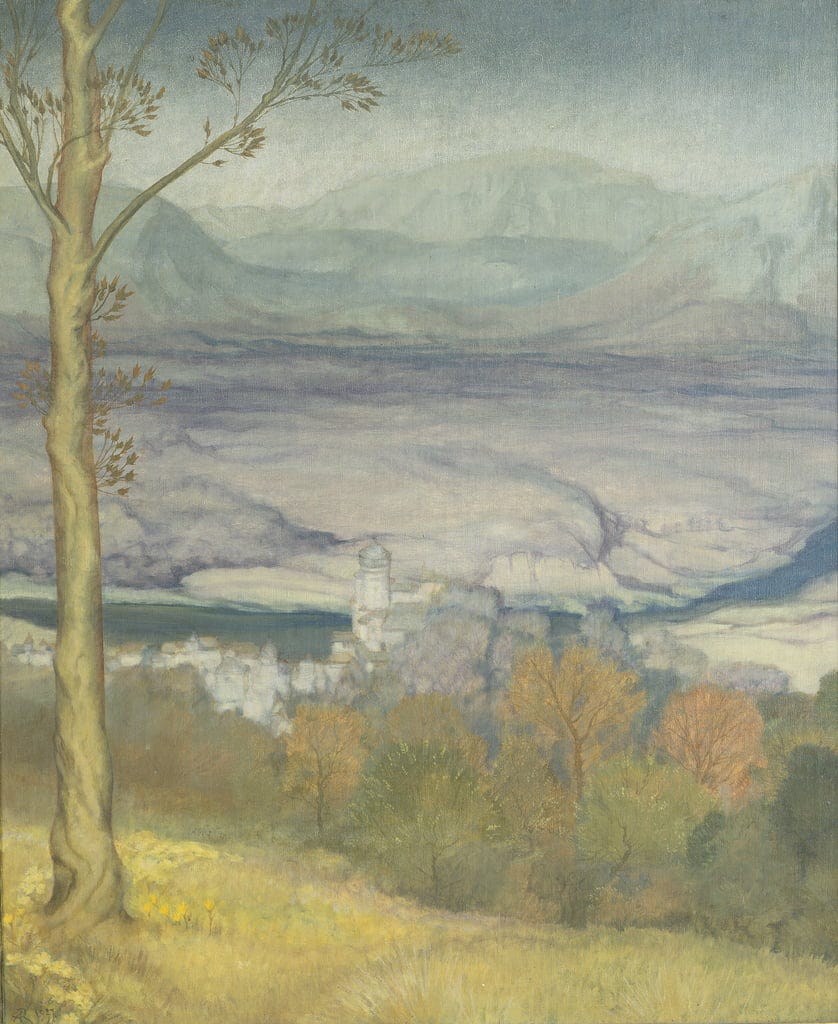

Late in his life, Rackham expressed that illustration had always been his “lesser aim,” while oil painting the ultimate and more “urgent” goal3. Yet we remember and love him for his imaginative illustrations; most of us have never even seen one of his oil landscapes. Rackham’s wife, Edith Starkie, herself an accomplished portrait artist and his severest critic, encouraged him to move away from strictly line illustrations and into painting.

Born in 1867 in London, Rackham was one of twelve children. As a child he had no formal art education, but he had a great love for art and constantly sketched animals and fantastic creatures to amuse himself. His parents noticed and took him often to art and natural history museums, where he would sit and draw. They also allowed him time to explore a 3-acre garden across the street from their home, where he was able to study nature attentively.

At 16, he left school and worked by day as a clerk and at an insurance company, while taking evening art classes at Lambeth School of Art.

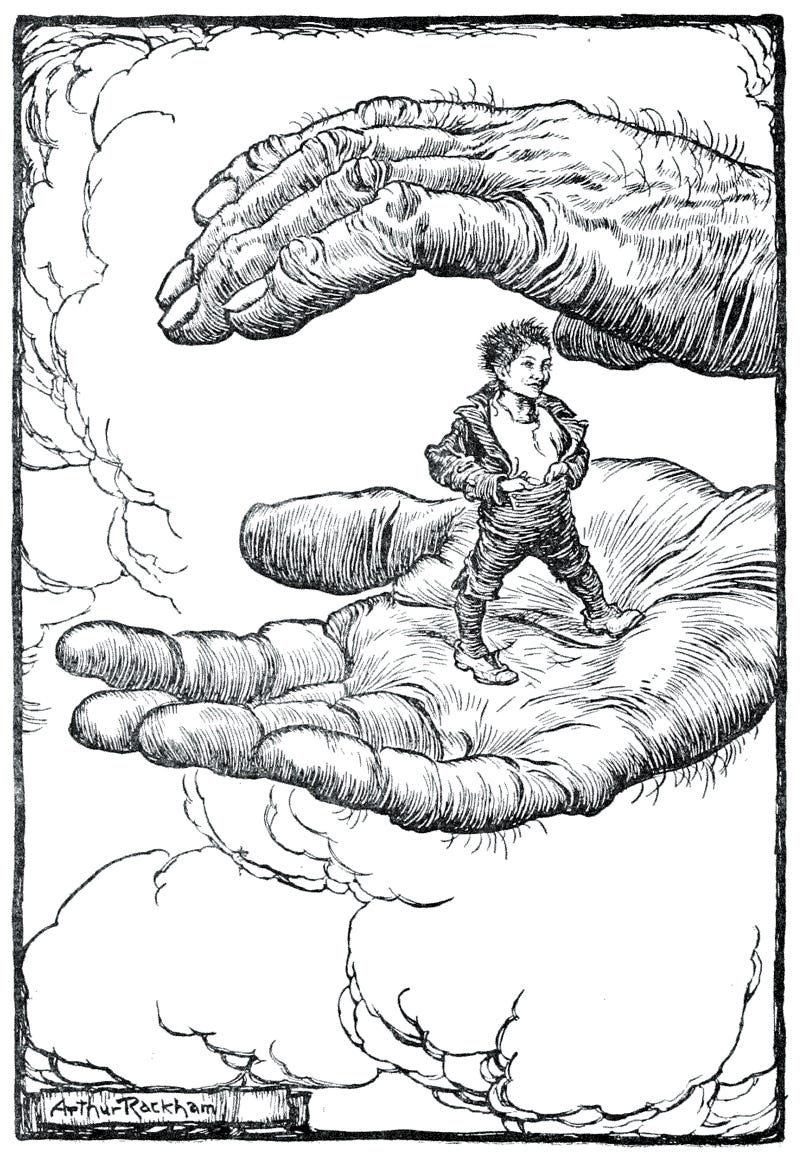

In 1892, at age twenty-five, Rackham began working as an artist full time. He began with journal illustrations and moved on to magazines and books, which became his lifelong career. He illustrated many books, including Peter Pan, Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Tempest, Rip Van Winkle, Lamb’s Tales From Shakespeare, Gulliver’s Travels, Aesop’s Fables, A Christmas Carol, and many, many others.

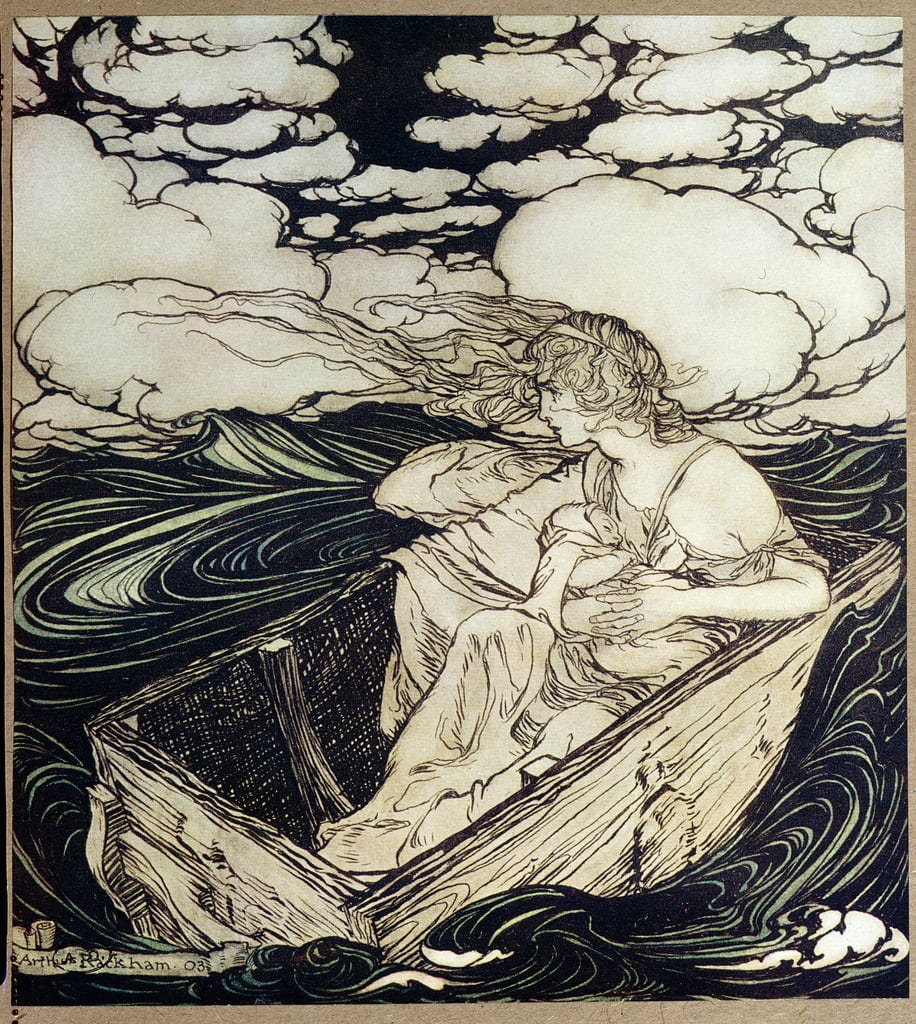

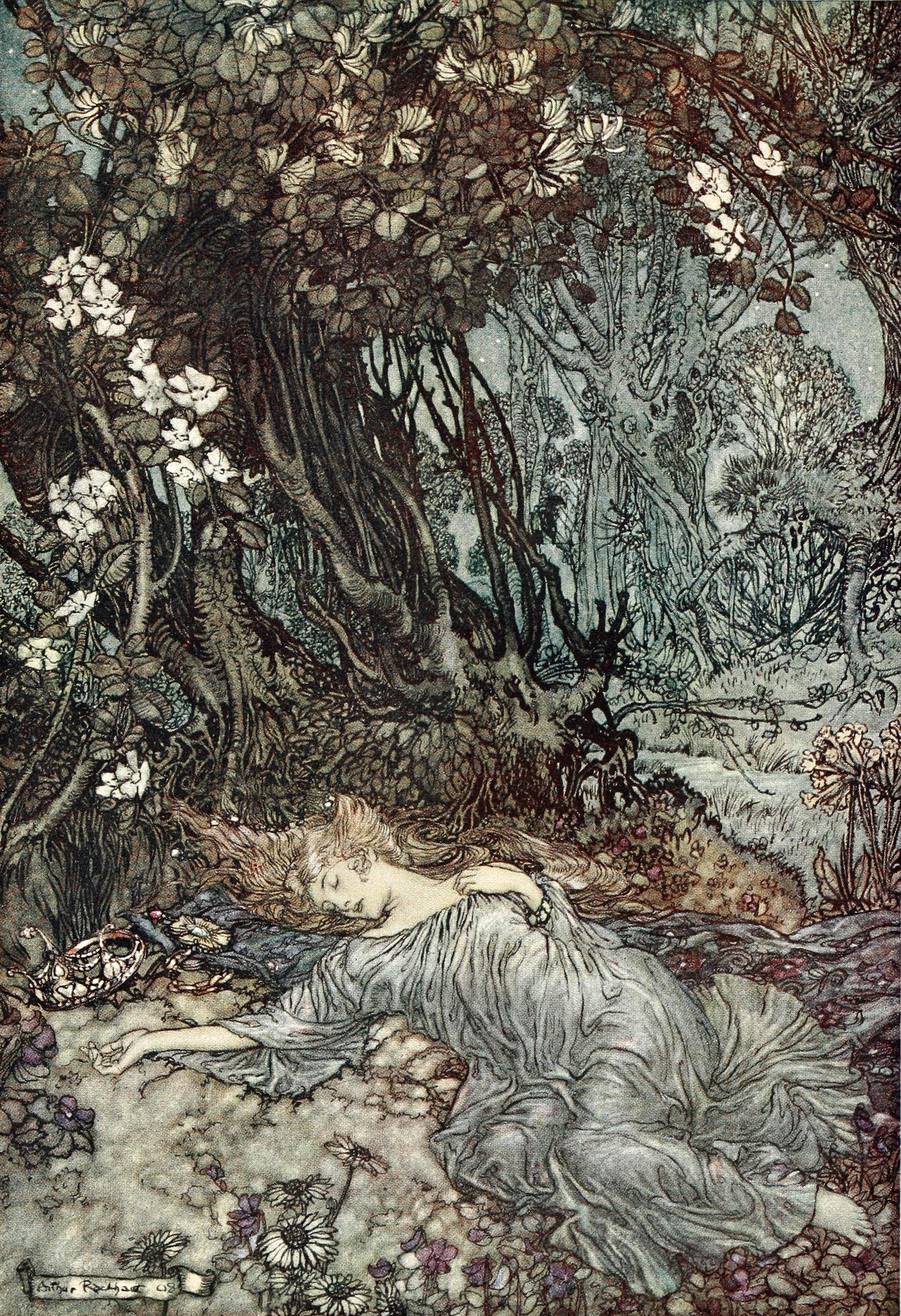

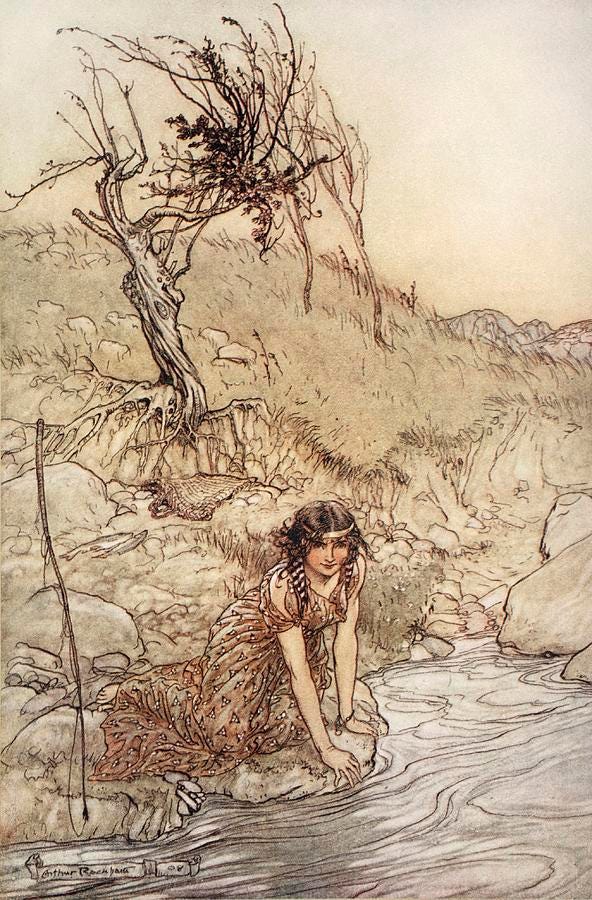

Rackham’s lack of early training allowed him to develop an artistic style that was uniquely his own—a magical, intricately detailed style with exquisite linework. He began each piece with pencil before going over the lines in ink. He then applied layer upon layer of watercolor, creating a haunting and dreamlike effect.

In 1908, Rackham turned down an offer to illustrate Kenneth Graham’s The Wind In The Willows in favor of illustrating A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This was a decision he would deeply regret for many years, but his depictions of the fairies in Midsummer have since informed the way the western imagination sees fairies: how they look and move and have their being.

Near the end of his life Rackham was given another chance to illustrate The Wind In The Willows, and he took it eagerly. Though sick and dying, Rackham worked feverishly through his exhaustion, insisting each drawing be exactly right, down to the last detail. The book was published posthumously in 1940.

Rackham’s art is hard to fit into a particular category. While he is certainly a “faithful and earnest interpreter” of nature, his artistic imagination goes well beyond realism, into something far more expansive. He “could not remain a realist, for realism would destroy all the spirit and meaning of his art”4.

The wonderful thing about art is that it has the ability to make us see the world through a different lens, precisely because it is not an exact reproduction of the natural world. An artist tells the truth about the world, but tells it “slant,” as Emily Dickinson says. He takes the world into his soul, and then pours it back as a new creation, like a vintner who takes grapes and gives them back to us as wine. And Arthur Rackham, whose soul was deep and imagination rich, offers us a wine that is transcendent.

Spending hours looking at Rackham’s artwork has certainly changed my own sight. I take a walk now and see his linework on the huge fifty-year-old oak trees on my street, their branches bare and black against the sky; I see his intricate lines and layers of watercolor in my oldest daughter’s wild and fairy-like hair.

Has this ever happened to you? In my research, I was happy to find I am not the only one. Eleanor Farjeon, in an article for Nicholas Magazine in 1914, had the same experience:

When the wizard shows us the delicate webs of leafless branches traced against a wintry sky, when he paints evening light for us, or pale marbled clouds, or patterns upon water, or children and and flowers as well as fairies in the Gardens—then he reveals a magic which Londoners may encounter day by day. And if, through years of apathy, we have grown numb to it, it is from Arthur Rackham that we may catch the angle of true vision again.

Hamilton, James. A Life With Illustration. Pook Press, 2017.

Yolen, Jane. Introduction. Grimm’s Complete Fairy Tales, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. Barnes & Noble, Inc., 2012.

Baldry, A. L. “Arthur Rackham: A Painter of Fantasies.” The Fantastic Line Art of Arthur Rackham, edited by Jeff A. Menges. Dover Publications, 2017.

Farjeon, Eleanor. “Arthur Rackham: The Wizard at Home.” The Fantastic Line Art of Arthur Rackham, edited by Jeff A. Menges. Dover Publications, 2017.

All of the illustrations you shared are incredible, but I especially enjoy “Jack Spratt and his wife”.

Arthur Rackham may be someone I need to study a bit more- thank you for bringing him to my attention!

Arthur Rackham has been my favorite artist since looking at my mom's old fairy books when I was a kid. I love all the artists from the 1920sand '30s, but he's still my fave. He does the best fairies and goblins... wish he could have done the Hobbit and LOTRs! No offense, JRR! I love your drawings too!